Study Suggests ‘Brain is to Blame’ for High Blood Pressure

By Deborah Borfitz

For decades, the pills used to treat high blood pressure have been targeting either the heart, kidneys, or blood vessels, missing the organ that is upstream of the problem, according to the paradigm-shifting discovery arising from a new study in rats co-led by Julian Paton, Ph.D., professor of translational physiology at the University of Auckland (New Zealand). “The brain is to blame for hypertension,” he confidently declares.

For at least 60% of all hypertensive patients, the culprit is likely “raised sympathetic activity that’s blasting away relentlessly,” predicts Paton. This always-on state of the sympathetic nervous system can be triggered by chronic intermittent hypoxia, a hallmark of obstructive sleep apnea, and begins with “expiratory oscillations” in the lateral parafacial region of the brain stem that also drive sympathetic activity raising its level (Circulation Research, DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.125.32667).

Suppressing neurons in this brain region could therefore represent a fresh approach to treating a causal mechanism (the high sympathetic activity) of high blood pressure rather than the symptoms, he says. Researchers now plan to test that hypothesis with a clinical trial using a Merck-owned drug, a purinergic receptor antagonist known as gefapixant (Lyfnua), which is already being prescribed for chronic cough in parts of Europe and Asia.

In parallel, the research team has a proof-of-principle study underway where they’re using a novel algorithm based on results of a DNA swab test for detecting variants within 17 genes known to control blood pressure, says Paton. The computational method is designed to predict which drug or drug combination would best suit individual hypertensive patients, so they’re prescribed the optimal medication “right off the bat.”

“Blood pressure is never fully diagnosed,” Paton explains, meaning treatment decisions are a bit of a guessing game for general practitioners (GPs). It often takes a long time to get patients’ blood pressure under control, mainly because they’re prescribed the wrong drugs.

Frontline “ABCD” anti-hypertensive medications—angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB)/converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics—can all lower blood pressure, but “none of those drugs, singularly or in combination, produce sustained reductions in sympathetic activity,” says Paton. “Sympathetic overactivity not only raises blood pressure, but it also produces end organ damage and is pro-inflammatory.”

The current empirical trial-and-error treatment approach to treating this largely symptomless disease often results in patients being filled up with unnecessary drugs and developing unwanted side effects, he points out. “So, what do patients do? They stop taking their drugs.”

Hypertension is often ineffectively treated on a global scale, says Paton. Only about 20% of hypertensive adults have the condition under control, based on the strict definition used by the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, leaving many of them at risk for stroke and heart disease.

Paton’s drug development and diagnostic work is being conducted concurrently as a matter of geography and clinical need, says Paton, who works closely with New Zealand’s many Māori and Pacific Peoples who are highly prone to cardiovascular disease and have a life expectancy seven years shorter than other New Zealanders. Those communities “are telling us what they need and in many cases helping with the design of studies so we can get proper representation” of the overall population into clinical trials.

Escalating Problem

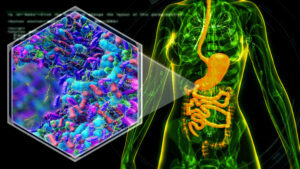

The big news here is identification of the lateral parafacial region as a contributor to elevated sympathetic activity in hypertension, says Paton. It was previously known primarily for generating active expiration, such as during coughing or exercise. The expiratory neurons in this region were found to be networked to sympathetic outflows. Sympathetic activity refers to that in the nerves connecting the brain to the blood vessels, heart, and kidneys, all of which are involved downstream in the generation of high blood pressure.

The lateral parafacial region controls forced exhalation, recruiting the abdominal muscles to help push air out of the lungs. Expiration is a passive process at rest, occurring when respiratory muscles relax, and the lungs utilize their natural elastic recoil to return to their original volume—no active muscle contraction required, he says.

The region causes the abdominal muscle pumping seen with active expiration and, by activating the central nervous system, raises blood pressure and drives the sympathetic circuits that initiate the “fight-or-flight” survival response. This is the body’s automatic reaction to fear, stress, or physical activity designed to rapidly boost alertness, energy, and cardiovascular function. “What we’ve found is a coupling between respiration and sympathetic nerves that cause high blood pressure,” says Paton.

This suggests that targeting lateral parafacial neurons could be a “potentially very powerful intervention to control blood pressure,” he adds. The hypertensive condition affects over 30% of the global adult population, and the problem is “only getting worse.”

About half of patients being treated with current medications don’t see their blood pressure lowered enough to derisk them for a cardiovascular event, Paton says. Epidemiological data also suggests that in conditions of stress blood pressure is escaping any pharmaceutical control.

In the future, Paton believes it will be necessary to understand blood pressure profiles in patients over a 24-hour period. It’s one thing to measure their static blood pressure when they’re sitting comfortably and relatively destressed in the doctor’s office, and quite another at its dynamic, variable level when they’re late for an appointment stuck in a traffic jam, he says. “It’s highly likely that any kind of mental or physical stress is pushing blood pressure up to enormously high, dangerous levels” that can trigger heart attacks and strokes.

While regular exercise is recommended for heart health, the dichotomy here is that people who have uncontrolled high blood pressure need to be careful about undertaking strenuous exercise such as “maximally trying to lift a weight or run up a steep hill,” says Paton. For this population, that degree of exertion can produce an exaggerated rise in blood pressure and heart rate that can lead to a cardiovascular event.

With chronic hypertension, as smooth muscle cells get bigger blood vessels lose their elasticity to absorb the pulse pressure wave, he explains. The stiffness creates enormous pulse pressures, “the difference between systolic pressure and diastolic pressure.”

The sympathetic nervous system also produces high levels of inflammation, compounding complications when trying to control blood pressure, Paton says. “We believe lowering sympathetic activity is not just going to relax blood vessels and help the heart contractility decrease but is also going to offset the sort of comorbidities that you get with inflammatory states.”

Clinical Need

The focus here is on essential hypertension, a syndrome of unknown origins that is characterized by a narrowing of arteries and responsible for up to 95% of all cases of high blood pressure, says Paton. The other 5% is termed secondary hypertension, which results from underlying conditions (e.g., enlarged adrenal gland) and can often be cured.

When arteries narrow, the only way organs can get enough blood flow is to raise blood pressure, he explains. This helps push blood through those constricted arteries. Many different subsets of essential hypertension exist, but his interest is neurogenic hypertension, and it is 60% of these patients that he suspects have raised sympathetic activity. This is not to say that there might be contributions from hormones such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system that is activated by the sympathetic nervous system, he adds.

“We’re looking at a very integrative problem here and we think if we reduce sympathetic activity, we can break a vicious feedback circuit” whereby sympathetic activity is driving up hormones, narrowing blood vessels, and raising the contractility and rate of the heartbeat, says Paton. “It’s a crucial target in the future control of blood pressure that’s not being controlled by frontline medications currently.”

Targeting the Carotid Bodies

In the latest study, the research aim was to come up with more focused treatment strategies and then determine how to target the identified region of the brain, says Paton. When the lateral parafacial region was deactivated in hypertensive rats, eliminating increases in sympathetic nervous system activity, blood pressure was normalized.

The implication is that changes in breathing patterns, such as forced and not passive expiration, can trigger high blood pressure. As breathing patterns are relatively easy to assess, this might assist doctors in diagnosing active abdominal breathing in patients with high blood pressure and assist in their choice of treatment, he says. The idea is supported by the fact that many patients with advanced heart failure are “belly pumpers,” referring to breathing that involves recruitment of the abdominal muscles when exhaling.

How to intervene in a way that is not invasive is the difficult part, says Paton. In animal models, the research team used optogenetics and viral vector shuttles to change the genetic profile of lateral parafacial neurons to make them express a light-sensitive protein. They allowed optogenetic techniques to selectively excite or inhibit their activity.

“We’re not yet at the stage of being able to perform targeted genetic manipulation of small groups of neurons … for controlling blood pressure in humans,” Paton says.

It could also be unnecessary. “The other big news here is that we don’t need to go into the brain for the lateral parafacial neurons because we know now what’s switching them on in hypertension is coming from the peripheral nervous system, [and] targeting something in the periphery is a lot easier than going into the brain,” he says. “It means that we can use drugs that are non-brain-penetrant and avoid side-effects.”

Paton and his colleagues have learned that the lateral parafacial neurons are being driven by the carotid body, a group of cells that reside in the neck at the point where the common carotid artery branches into external and internal branches. “The carotid body is about the size of a rice grain and there’s one on each of the carotid arteries in the neck, and they have nerves that go directly into the brain,” Paton says. “When you stimulate those nerves from the carotid body, they activate the lateral parafacial region.”

With hypertension, those carotid bodies become activated for some reason and lead to overactivation of the lateral parafacial region, he continues. “We are proposing not to form an intervention at the lateral parafacial neurons but … outside the body by targeting the carotid bodies.”

The research team knows from many years of prior work that what is making the carotid bodies super-active in hypertension is the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), says Paton, which is both an energy molecule and neurotransmitter.

Drug Repurposing

In the upcoming clinical trial, researchers will use Lyfnua to block the specific receptor for ATP that attenuates activity in the carotid bodies in hopes of lessening lateral parafacial and sympathetic activity, and thereby reducing blood pressure, Paton reports. Initial trials for the drug as a chronic cough medicine were led by Antony Ford, Ph.D., former chief scientific officer at Afferent Pharmaceuticals, acquired by Merck in 2016.

Lyfnua acts by inhibiting the mechanism that causes laryngeal hypersensitivity, which later studies by Paton and Ford successfully extended to resetting overactivity of the carotid bodies. “You don’t have to remove the carotid bodies,” Paton notes, “as this drug merely removes the pathological signaling.” The carotid bodies serve as an oxygen and carbon dioxide sensor and stimulate breathing, so it’s important that they be intact, just not hyperactive.

The original 2016 proof-of-concept studies demonstrating that the carotid bodies are controlling and producing high blood pressure involved patients with refractory hypertension (over 180 systolic blood pressure) even after taking five or more anti-hypertensive medications, he says. Study participants consented to have one of their carotid bodies removed.

In a subset of those patients, researchers showed the carotid bodies were hyper-sensitive and, when their carotid body was removed, ambulatory blood pressure dropped dramatically—by about 25 mmHg, which is about three times more than an anti-hypertensive drug can achieve, says Paton. Sympathetic activity was also lowered, but at the time they didn’t realize that the entire interconnected process was being channeled through the lateral parafacial nucleus.

Paton is involved in an ongoing trial in the UK where Lyfnua is being investigated as a treatment for patients with long COVID syndrome. “These patients are hyperventilating and, since the carotid body stimulates breathing, we thought it would be really useful to see if Lyfnua would help control their breathing, because if you hyperventilate you lose carbon dioxide, your brain blood flow decreases, and you end up with brain fog and feel miserable.” This trial has just started.

The trial of Lyfnua for treating patients with high blood pressure awaits financial support but needs funding to proceed, he reports. Sympathetic activity is to be measured directly via microneurography, a technique whereby a fine recording microelectrode the size of an acupuncture needle gets directed into the peroneal nerve running along the side of the knee. “We can find sympathetic nerves in that peroneal nerve bundle that are going to the arteries in the muscle in the lower part of the leg” since they have a unique firing pattern.

Only about 20 patients will be needed for the first-in-human study to demonstrate a statistical change in blood pressure from the drug, he adds, and positive findings would spur larger, multi-site trials. “There are great advantages to using a repurposed drug,” he observes, including established safety and pharmacokinetic data and accelerated development timelines.

Sleep Apnea Connection

The preclinical study involved rats placed in an environment of intermittent hypoxia (low oxygen bouts) to partially mimic patients with sleep apnea. “The hypoxia generated is the most powerful stimulus for the carotid bodies.”

A lot of work has been done in patients with sleep apnea targeting the carotid bodies, typically transiently, he continues. There are many ways to inactivate the carotid bodies noninvasively, such as oxygen therapy and pharmacological agents, and thereby lower patients’ sympathetic activity and restoring their blood pressure.

The proposed Lyfnua study won’t necessarily be in patients with sleep apnea, at least initially, but may well include some such individuals given the crossover between hypertension and the breathing disorder, Paton adds. Subsequent trials “could definitely” explore the possibility that the drug can attenuate some forms of sleep apnea through better blood gas regulation.

Currently, sleep apnea is treated primary with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device rather than drugs, he says. The machine is not well tolerated and has high discontinuation rates, which is problematic given that a clinically meaningful reduction in blood pressure is tied to at least six hours of CPAP use for five or six nights per week.

Paton sees a major market opportunity in this realm. “I’m not necessarily saying we’ll be able to treat all sleep apnea, particularly some of the obstructive apneas that you get in obese patients.” But reducing carotid body activity could potentially help with central apneas, where the brain fails to signal the muscles to breathe, and mixed central apneas, characterized by a lack of breathing effort followed by an obstruction as breathing resumes.

Final Word

For Paton, one of the big takeaways here that would make a sizable difference in world health is simply this: “Measure your blood pressure … that’s the starting point.” It is relatively easy to do, and, if a blood pressure machine is unaffordable, the local pharmacy, supermarkets and GP clinics often have them freely available for use.

“Blood pressure contributes to cardiovascular risk more than any other risk factor,” including high salt consumption, smoking, lack of exercise, alcohol, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides, age, obesity, and genetic inheritance, he points out. If none of those other risk factors are at play, “the body can probably tolerate a little bit of blood pressure above normal.” But combining any one of them with high blood pressure “exponentially increase your chances of a cardiovascular event.”

Countries around the world are “spending an absolute fortune” treating heart attacks, strokes, and chronic kidney diseases. Particularly in places like the U.S., where healthcare costs are especially high, “people need to be proactive about their health” and do what they can to reduce their own risk.

It would also be good if patients, when talking with their clinicians, started reinforcing the idea that “there is a central nervous component to high blood pressure,” says Paton, to get them to move away from the dogma that it’s all about the kidneys. “It is to a point, but it’s not the full story.”