Vermont Medicaid Acupuncture Pilot produces positive results and possible action

By John Weeks

by John Weeks, Publisher/Editor of The Integrator Blog News and Reports

by John Weeks, Publisher/Editor of The Integrator Blog News and Reports

Editor’s note: This analysis article is not edited and the authors are solely responsible for the content. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Integrative Practitioner.

In mid-2016, the Vermont legislature made a $200,000 research investment in acupuncture to support its potential value as a covered service in pain treatment for the state’s Medicaid population. Of chief concern was opioid abuse. The report to the legislature of the outcomes are now in. On the headliner outcome, 38% of those on opiates were able to decrease them during the trial.

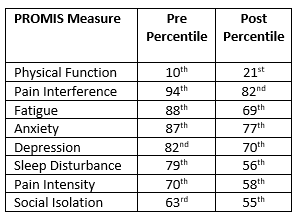

The legislative move was action focused and on a tight time frame. The research team, led by Robert Davis, MS, LAc, a co-president of the Society for Acupuncture Research, chose a pragmatic, uncontrolled, prospective intervention design . In a presentation of the results at University of Vermont Medical Center, Davis began with data about the study participants. On PROMIS self-report scales at the beginning of the study, physical function was quite low, in the 10th percentile. On seven others that looked at complaints, the percentiles were quite high. These ranged from Social Isolation at 63rd percentile up to Pain Interference in the 94th. Fatigue, anxiety and depression were all above the 82nd percentile. Notably, the study did not limit patients to a certain type of pain. Instead, to increase the “real world” generalizability of the data, it included a heterogeneous group of patients with chronic pain as well as other comorbidities.

The legislative move was action focused and on a tight time frame. The research team, led by Robert Davis, MS, LAc, a co-president of the Society for Acupuncture Research, chose a pragmatic, uncontrolled, prospective intervention design . In a presentation of the results at University of Vermont Medical Center, Davis began with data about the study participants. On PROMIS self-report scales at the beginning of the study, physical function was quite low, in the 10th percentile. On seven others that looked at complaints, the percentiles were quite high. These ranged from Social Isolation at 63rd percentile up to Pain Interference in the 94th. Fatigue, anxiety and depression were all above the 82nd percentile. Notably, the study did not limit patients to a certain type of pain. Instead, to increase the “real world” generalizability of the data, it included a heterogeneous group of patients with chronic pain as well as other comorbidities.

The 156 patients who were enrolled (71% female) could receive up to 12 visits (average 8.1) over the 60-day period of the trial. Care was provided in a real world setting in the offices of 28 licensed acupuncturists. Thirty-eight percent of the subjects completed the whole series of 12 visits. Nearly three-fourths had at least six. Such fluctuations reflected the real-world intentions.

The 156 patients who were enrolled (71% female) could receive up to 12 visits (average 8.1) over the 60-day period of the trial. Care was provided in a real world setting in the offices of 28 licensed acupuncturists. Thirty-eight percent of the subjects completed the whole series of 12 visits. Nearly three-fourths had at least six. Such fluctuations reflected the real-world intentions.

Key findings on the effect on pharmaceutical usage were that of the nearly one-third of the subjects on opioids when the trial began, 32% decreased their use. Of those using any pain killer, 57% were able to decrease their use. The patient self-reports on the PROMIS measures showed significant positive improvement across all 8 measures.

In addition, the trial produced valuable practical data in an array of other areas that bode well for an increased role for acupuncture:

- given the quick sign-up for the pilot, clear evidence of interest in the Medicaid population in using acupuncture;

- similarly, comfort with medical doctors in referring patients for acupuncture; and

- availability of licensed acupuncturists to provide services at the pilot project’s rates ($125 for initial visit and $65 for follow-up visits).

Findings on cost were generally inconclusive. While the investigators found some diminished service utilization and a general downward trend in costs, the report notes that “analysis of Medicaid claims data led to no findings of statistical significance.” Of note, however, to employers, is that 59% of the subjects said they believed they had better work performance following the acupuncture treatment.

Findings on cost were generally inconclusive. While the investigators found some diminished service utilization and a general downward trend in costs, the report notes that “analysis of Medicaid claims data led to no findings of statistical significance.” Of note, however, to employers, is that 59% of the subjects said they believed they had better work performance following the acupuncture treatment.

A media account following the report to the legislature included positive but inconclusive comments from legislative leaders. There are no firm decisions. A leader with the Vermont Medical Association opines favorably that as medical doctors “are prescribing fewer and fewer opioids, alternatives such as acupuncture could be more widely used.” The chief medical officer for the Department of Vermont Health Access, Scott Strenio, MD, while acknowledging the strong positive response from the users, adds: “I don’t think it was a compelling case that acupuncture led to a decrease in opiate use.”

Comment: Davis and his advisers on the study design – drawn from the Society for Acupuncture Research – decided on a “pragmatic trial” as Davis describes in this invited commentary in JACM (Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine). The legislature had and still has a pressing, present problem with opioids. They wanted guidance quickly. So Davis and the SAR team concluded it was not time for basic research or a double-blinded, randomized and controlled trial. Instead, how about information on patient experience – for this era of patient-centered care – and on costs. Is the intervention an effective alternative to opioids and pain pills? What they wanted, as Davis’ explanatory commentary put it, was “evidence to inform policy.”

The results, as assessed by Vermont Health Access’s Strenio – one of the study’s targeted decision-makers – were inconclusive. The study may simply have been too small, or too short, to yield meaningful data on costs and reduction in use of opioids in this populations. However, this was never the study’s intention. According to Davis, the study was never designed to answer questions regarding acupuncture’s impact on opiate use. If it were, it would’ve only accepted opiate users into the trial. Rather, it was designed to see whether and how the services of licensed acupuncturists could fit into the multiple means the state recognizes for addressing chronic pain.

The results, as assessed by Vermont Health Access’s Strenio – one of the study’s targeted decision-makers – were inconclusive. The study may simply have been too small, or too short, to yield meaningful data on costs and reduction in use of opioids in this populations. However, this was never the study’s intention. According to Davis, the study was never designed to answer questions regarding acupuncture’s impact on opiate use. If it were, it would’ve only accepted opiate users into the trial. Rather, it was designed to see whether and how the services of licensed acupuncturists could fit into the multiple means the state recognizes for addressing chronic pain.

Another audience of decision-makers is the funding agency, the legislature and its charge to serve its citizens. Legislators may be more likely to be moved by the comments from participants included in the report, and in the news account. “This is the longest I’ve gone without pain or medication in well over a year,” wrote one. Another wrote: “If it had been covered, I may not have gotten so many scripts of narcotics and gotten addicted to opiates.”

According to the news account, the chair of the relevant Senate Committee on Health and Welfare, Claire Ayer, D-Addison, “wants to see a more conclusive study, and cooperation from insurance companies, before her committee moves forward on acupuncture.” Then she shrugs, noting that the current situation offers Medicaid patients little choice. They can take insurance covered opioids, or pay for acupuncture treatments with their own money: “What kind of choice is that?”

Without insurance coverage for acupuncture or other non-pharmacologic approaches, Ayer and her colleagues will effectively force Vermont’s underserved down this sieve toward opioids. Yet following this practical trial, legislators now have a clearer choice of their own. They have multiple practical pieces of the puzzle together on the roles of licensed acupuncturists in optimal pain care. Perhaps it is time to err on the side not of exclusion, but of inclusion, and thus of consumer and clinician choice of acupuncture in their treatment of their chronic pain. If it should prove to be a poor decision, the loss will be measured in dollars and not, as is currently the case, in lives burdened and lost.