Rethinking Adrenal Fatigue: An Evidence Based Review of Hypocortisolism

By Lena Edwards

The stress response system (SRS) truly rivals the natural wonders of the world in its purpose and level of complexity. This sophisticated neurobiological network coordinates all physiological processes and maintains internal balance, or homeostasis, in unpredictable or potentially threatening environments1–3. Unfortunately, the SRS has not evolved quickly enough to accommodate the ‘human condition’, a dilemma not encountered by other organisms. Gifted with independent thought, advanced cognition, and the capacity to express emotion, humans can act and react outside of the primitive confines of the innate ‘fight or flight’ response. Moreover, a plethora of superimposed endogenous and exogenous factors have been shown to alter basal and stress induced SRS activation4–10. Consequently, the human SRS is constantly immersed in an unfamiliar and ever-changing physiologic landscape which can ultimately overwhelm its adaptive capacity.

The SRS is not a linear system originating in the hypothalamus and terminating in the adrenal glands. Rather, this extremely sophisticated system houses numerous other structures, organ systems, chemical mediators, and hormonal modulators whose collaborative efforts drive basal and stress induced SRS function3,11,12. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a vital component of the SRS in so far as its effector hormone, cortisol, has widespread influence in regulating all metabolic processes as well as in determining basal SRS tone. However, it is the elaborate system of checks and balances imposed by other equally influential members of the SRS which prevents autonomous HPA axis hyperactivation and glucocorticoid (GC) induced catabolic tissue damage3,6,11,12.

The origins of hypocortisolism are extremely complex and can reflect temporary or permanent impairment in innate HPA axis function under the influence of countless tangential factors. These factors are unique not only to the individual but also to the stressor itself, and their influence determines the presence, severity, duration, and clinical manifestations of hypocortisolism4,8,10,13,14. In viewing the highly convoluted nature of the HPA axis through this lens, it is reasonable to question the anecdotal notion of “adrenal fatigue.” Despite the lack of scientific validation supporting its existence, adrenal fatigue continues to be widely accepted as a legitimate clinical diagnosis by many medical practitioners and patients who contend that chronic stress can induce hypocortisolism through autonomous adrenal gland ‘exhaustion’ outside of other regulatory controls15. This concise review will highlight the primary mechanisms through which hypocortisolism can arise and the clinical consequences thereof.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Hypocortisolism

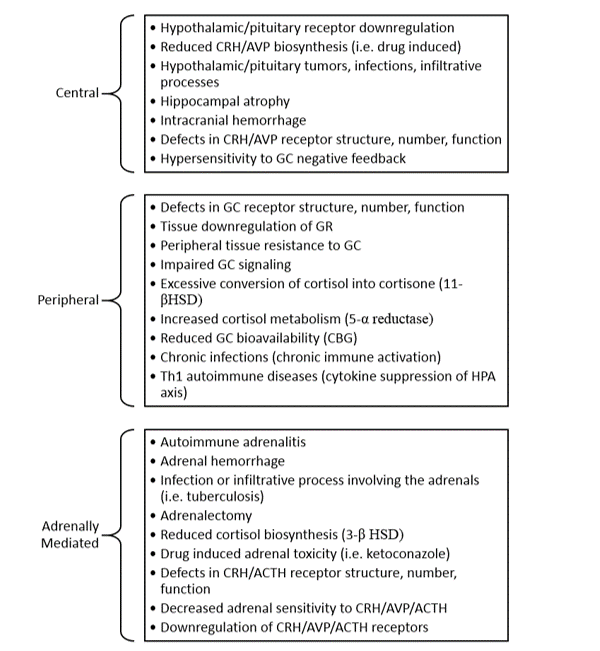

Basal and stress induced cortisol levels can be compromised by any process which impairs the structural or functional integrity of one or more components of the HPA axis. These conditions can be classified under the categories of primary, secondary, or tertiary adrenal insufficiency depending upon whether the disruption occurs at the level of the adrenal glands, the pituitary gland, or the hypothalamus, respectively16. However, relative states of cortisol insufficiency can exist absent conditions that impair one or more components of the HPA axis. Such is the case when cortisol bioavailability is reduced or if tissue sensitivity to cortisol is impaired (Table 2) 3,3,4,6,8,11,13,16–21.

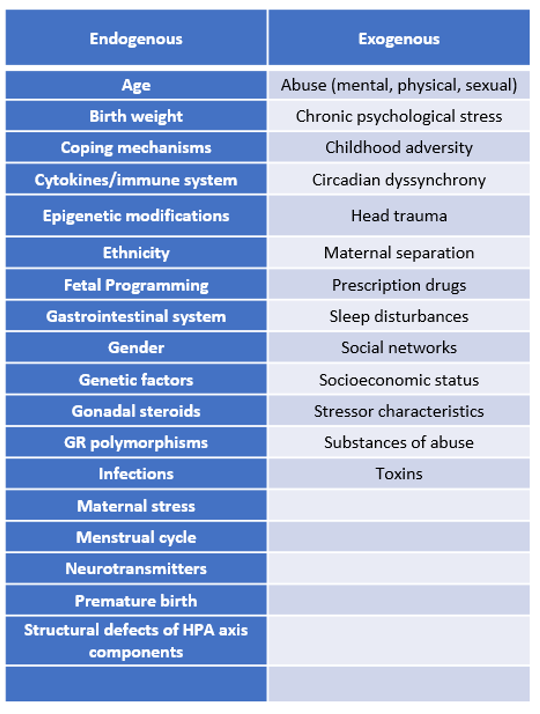

In contrast with cortisol insufficiency, hypocortisolism broader in its scope and further encompasses variations in basal and stress induced cortisol release patterns. Hypocortisolism can manifest as a flattened diurnal cortisol release pattern, a blunted cortisol response to awakening, and/or an insufficient stress induced rise in cortisol levels4,10. The mechanisms through which hypocortisolism evolves remain unclear but differ from those which give rise to absolute cortisol insufficiency. The process is further complicated by the fact that innate HPA axis function can be continuously, and in some cases permanently, altered through exposure to countless endogenous and exogenous factors (Table 1). Thus, hypocortisolism can evolve at different times and manifest in a variety of ways in the same individual or in similar individuals who are subjected to the same or different stressors14.

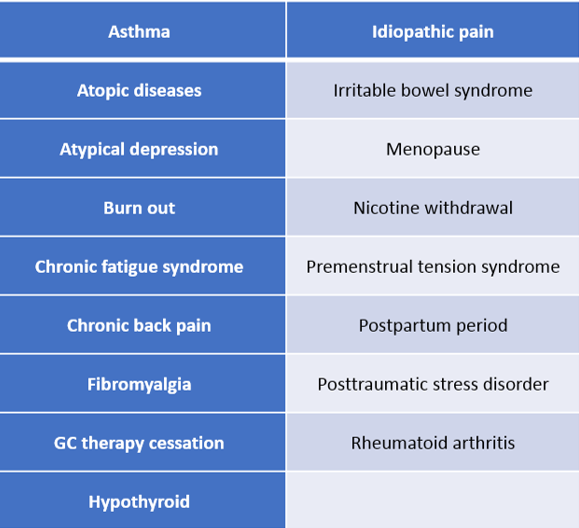

The paradoxical phenomenon of hypocortisolism has challenged the longstanding belief that chronic stress uniformly causes HPA axis hyperactivation. Hypocortisolism was first confirmed in otherwise healthy individuals living under conditions of chronic stress10. However, the pivotal work of Yehuda and colleagues in 1997 confirmed that chronic stress exposure, in this case in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), could induced blunting of HPA axis activation22. Subsequent research replicated their findings and additionally demonstrated an association between hypocortisolism and other adult stress related bodily disorders, including chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), ‘burn out’ and fibromyalgia (FMS)4,10,23–27.

The foundational groundwork established by Heim, Fries, and other pioneers in stress research has provided invaluable insight into the potential mechanisms leading to chronic stress induced hypocortisolism. The majority of research suggests that the presence of hypocortisolism during chronic stress exposure likely results from excessive cortisol mediated downregulation, mainly at the pituitary level4,10,13,22,28,29. Adrenally mediated hypocortisolism has also been demonstrated, however it is occurs subsequent to downregulation of adrenal CRH, AVP, and ACTH receptors rather than to autonomously mediated ‘adrenal fatigue’4,8,10,23,24,29–36.

Notwithstanding, studies observed that hypocortisolism can be exaggerated by the duration of stress exposure as well as the number and intensity of the concomitant stressors1,2,4,13,27,37,37,38.

It remains unclear whether hypocortisolism occurs as a maladaptive response or as an adaptive mechanism to protect the metabolic machinery from unregulated cortisol mediated tissue damage4,10,26,39. Research conducted on pregnant mothers supports the contention that maternal hypocortisolism serves as adaptive safeguard to protect fetal HPA axis growth and development40,41. Hypocortisolism observed in those who are critically ill or suffer from chronic infections is also believed to reflect an adaptive counter maneuver to facilitate upregulation of immune defenses in the face of ongoing threat4,42–47.

Hypocortisolism and Stress Related Bodily Disorders

Much of the research on hypocortisolism has been conducted in children who experienced traumatic life experiences, including neglect, parental loss or separation, abuse of any kind, institutionalization, natural disasters, and acts of violence13,29,31,35,37,38,48–51. The development of hypocortisolism during childhood has been associated with higher incidences of abnormal growth and development as well as mood disorders, substance abuse, behavioral disorders, and cognitive dysfunction29,31,37,38,48,49,52. Moreover, the degree to which these conditions manifest clinically appears to be directly related to the duration and timing of exposure, the nature of the stress, and the timing between assessment and the stress exposure. In fact, the evidence suggests that earlier and more intense the stress exposure, the greater the risk of permanent alteration in the “set point” of the HPA axis, and the more likely hypocortisolism will persist into adulthood8,29,34,38,52,53.

Adult hypocortisolism, whether newly emerging or persistent from childhood, has been associated with the development of certain stress related bodily disorders, some of which are listed in Table 3. In fact, it has been suggested that approximately 25 percent of individuals suffering from stress related bodily disorders have associated hypocortisolism4. Significant overlap has been observed in the clinical symptomatology of stress related bodily disorders, and this is most likely due to the similar pathophysiological processes which give rise to them4,10,22,24–26,36,54–57. Fries and colleagues coined the term “hypocortisolism triad” to describe the three most prevalent symptoms observed in stress related bodily disorders, namely chronic fatigue, chronic pain, and stress sensitivity4.

PTSD is one of the most well-studied stress related bodily disorders. It is characterized by symptoms of avoidance, reexperience of the traumatic event, and hyperarousal58. Studies in both children and adults suffering from PTSD demonstrated not only impairments in HPA axis function but in immune system function as well. Some of these findings include:

- Low baseline cortisol secretion

- Increased GR binding to lymphocytes

- Enhanced GC negative feedback on ACTH

- Flattened diurnal cortisol release patterns

- Blunted ACTH responses to CRH4,10,22,26,36,59

Increased levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNFα, have also been demonstrated and are believed to contribute to the fatigue, pain, depression, and sleep disturbances frequently seen in these individuals10,22,26,29,36,57,58. It has been suggested that the extent to which PTSD occurs or persists may be dependent upon the stressor characteristics and the presence concomitant life stressors60. However, individuals who develop hypocortisolism shortly after a traumatic event appear to be more vulnerable to developing subsequent PTSD22,61.

CFS is another stress related bodily disorder, which has been strongly associated with hypocortisolism25,54. This condition is characterized by persistent fatigue lasting at least six months with at least four of eight additional symptoms54. As in PTSD, concomitant elevations in proinflammatory cytokines contribute to symptoms of malaise, depressed mood, sleep disturbances, and stress sensitivity25,30. It has been suggested that CFS may represent a form of subclinical Addison’s Disease given the significant overlap in symptomatology as well as the presence of hypocortisolism in both conditions62,63. However, it remains unclear whether CFS occurs as a consequence of hypocortisolism or if hypocortisolism evolves as a delayed clinical consequence related to the symptomatic changes associated with CFS25. Some studies have even suggested that the hypocortisolism observed in stress related CFS is the consequence of a HPA axis switch, whereby stress induced HPA axis hyperactivation eventually transforms into hypoactivation under the strain of ongoing stress, illness, or infection30,64.

Conclusion

The human SRS is a vast and incredibly sophisticated neuroendocrine network designed to maintain physiologic homeostasis and orchestrate diurnal metabolic functions. Under normal circumstances, the SRS is a dynamic system and exhibits a certain degree of regulatory flexibility. However, if the its baseline function is exogenously modified or its adaptive capacity is overwhelmed, the very system designed to maintain homeostasis can become the instrument of widespread physiologic chaos.

Addison’s Disease and Cushing’s Disease have long represented the clinical extremes of cortisol production. However, extensive research has since broadened our understanding of the HPA axis and the many factors which can modify its capacity and functional integrity. We now know that more subtle versions of hyper- and hypocortisolism manifest clinically and can arise through mechanisms, which do not directly affect the structural integrity of one or more components of the HPA axis. Furthermore, the presence and extent to which innate HPA axis function is altered is preordained by antenatal factors and continuously reconfigured by countless environmental modifiers.

The paradoxical observation of stress induced hypocortisolism serves as a testament to the extremely complex nature of the SRS. Moreover, the clinical relevance of hypocortisolism can no longer be discounted because of its association with stress related bodily disorders. However, an evidence-based approach to hypocortisolism is of paramount importance if diagnostic and therapeutic measures are to be properly implemented. To this end, we offer the following summary of the scientific evidence:

- Chronic stress exposure can give rise to hypocortisolism through adaptive downregulation of the central components HPA axis

- Hypocortisolism has been associated with stress related bodily disorders but can also exist in asymptomatic individuals living in chronically stressful environments

- Hypocortisolism can reflect an adaptive counter maneuver designed to enhance immune defenses during periods of critical illness, trauma, or infection

- In the event that hypocortisolism is adrenally mediated, it occurs after downregulation of adrenal AVP, CRH, and ACTH receptors, not through autonomously mediated “adrenal fatigue.”

Tables

Table 1: Factors Affecting HPA Axis Function and Cortisol Levels

Table 2: Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Hypocortisolism

Table 3: Clinical Conditions Associated with HPA Axis Hypofunction

References

- McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Europ J Pharmacol. 2008;583(2-3):174-185.

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. NEJM. 1998;338(3):171-179.

- Chrousos GP. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(7):374-81.

- Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2005;30(10):1010-1016.

- Van Cauter E, Leproult R, Kupfer DJ. Effects of gender and age on the levels and circadian rhythmicity of plasma cortisol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(7):2468-73.

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):865-71.

- John CD, Buckingham JC. Cytokines: regulation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3(1):78-84.

- Raison CL, Miller AH. When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Amer J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1554-1565.

- De Weerth C. Do bacteria shape our development? Crosstalk between intestinal microbiota and HPA axis. Neurosci Biobehavior Rev. 2017.

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(1):1-35.

- Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:259-284.

- Papadimitriou A, Priftis KN. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Neuroimmunomod. 2009;16(5):265-271.

- Gunnar MR, Vazquez DM. Low cortisol and a flattening of expected daytime rhythm: Potential indices of risk in human development. Development and psychopathology. 2001;13(3):515-538.

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Wüst S. Why do we respond so differently? Reviewing determinants of human salivary cortisol responses to challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(1):2-18.

- Wilson JL. Clinical perspective on stress, cortisol and adrenal fatigue. Adv Integrative Med. 2014;1(2):93-96.

- Charmandari E NN, GP C. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2152-2167.

- Buijs RM, Scheer FA, Kreier F et al. Organization of circadian functions: interaction with the body. Prog Brain Res. 2006;153:341-60.

- Chrousos GP. Organization and integration of the endocrine system: the arousal and sleep perspective. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2(2):125-145.

- Chrousos GP, Kino T. Glucocorticoid signaling in the cell. Expanding clinical implications to complex human behavioral and somatic disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1179:153-66.

- Gold P, Chrousos G. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Molecular Psych. 2002;7(3):254.

- Lanterna LA, Brembilla C, Gritti P. Hypocortisolism: An Underestimated Complication of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(5):e665.

- Yehuda R. Sensitization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;821(1):57-75.

- Gur A, Cevik R, Sarac A, Colpan L, Em S. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and cortisol in young women with primary fibromyalgia: the potential roles of depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in the occurrence of hypocortisolism. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2004;63(11):1504-1506.

- Demitrack MA, Crofford LJ. Evidence for and pathophysiologic implications of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;840(1):684-697.

- Cleare AJ. The HPA axis and the genesis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15(2):55-9.

- Ehlert U, Gaab J, Heinrichs M. Psychoneuroendocrinological contributions to the etiology of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and stress-related bodily disorders: the role of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Biol Psych. 2001;57(1-3):141-152.

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873-904.

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hanker JP, Hellhammer DH. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder and alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosomatic medicine. 1998;60(3):309-318.

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Bonsall R et al. Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Am J Psych. 2001;158(4):575-581.

- Van Houdenhove B, Van Den Eede F, Luyten P. Does hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hypofunction in chronic fatigue syndrome reflect a “crash” in the stress system? Med Hypotheses. 2009;72(6):701-5.

- Kuras Y, Assaf N, Thoma MV et al. Blunted Diurnal Cortisol Activity in Healthy Adults with Childhood Adversity. Front Human Neurosci. 2017;11:574.

- Waller C, Bauersachs J, Hoppmann U et al. Blunted cortisol stress response and depression-induced hypocortisolism is related to inflammation in patients with cad. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1124-1126.

- Lennartsson A-K, Sjӧrs A, Währborg P et al. Burnout and hypocortisolism-a matter of severity? A study on ACTH and cortisol responses to acute psychosocial stress. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:8.

- Rich EL, Romero LM. Exposure to chronic stress downregulates corticosterone responses to acute stressors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(6):R1628-36.

- Lovallo WR, Farag NH, Sorocco KH et al. Lifetime adversity leads to blunted stress axis reactivity: studies from the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns Project. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(4):344-9.

- Rohleder N, Joksimovic L, Wolf JM, Kirschbaum C. Hypocortisolism and increased glucocorticoid sensitivity of pro-Inflammatory cytokine production in Bosnian war refugees with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psych. 2004;55(7):745-751.

- Koss KJ, Mliner SB, Donzella B, Gunnar MR. Early adversity, hypocortisolism, and behavior problems at school entry: A study of internationally adopted children. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2016;66:31-38.

- Van Voorhees E, Scarpa A. The effects of child maltreatment on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2004;5(4):333-352.

- Hellhammer J, Schlotz W, Stone A, Pirke K, Hellhammer D. Allostatic load, perceived stress, and health: a prospective study in two age groups. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1032(1):8-13.

- Weinstock M. The potential influence of maternal stress hormones on development and mental health of the offspring. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(4):296-308.

- Del Giudice M. Fetal programming by maternal stress: Insights from a conflict perspective. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(10):1614-29.

- Widmer IE, Puder JJ, König C et al. Cortisol response in relation to the severity of stress and illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4579-86.

- Ok YJ, Lim JY, Jung S-H. Critical Illness-Related Corticosteroid Insufficiency in Patients with Low Cardiac Output Syndrome after Cardiac Surgery. Korean J Thoracic Cardivasc Surg. 2018;51(2):109.

- Yang Y, Liu L, Jiang D et al. Critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency after multiple traumas: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(6):1390-6.

- Koene R, Catanese J, Sarosi G. Adrenal hypofunction from histoplasmosis: a literature review from 1971 to 2012. Infection. 2013;41(4):757-759.

- Ekpebegh CO, Ogbera AO, Longo-Mbenza et al. Basal cortisol levels and correlates of hypoadrenalism in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Med Princip Pract. 2011;20(6):525-529.

- O’connor T, O’halloran D, Shanahan F. The stress response and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: from molecule to melancholia. QJM. 2000;93(6):323-333.

- Gonzalez A, Jenkins JM, Steiner M, Fleming AS. The relation between early life adversity, cortisol awakening response and diurnal salivary cortisol levels in postpartum women. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2009;34(1):76-86.

- Juruena MF. Early-life stress and HPA axis trigger recurrent adulthood depression. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;38:148-159.

- Hunter AL, Minnis H, Wilson P. Altered stress responses in children exposed to early adversity: a systematic review of salivary cortisol studies. Stress. 2011;14(6):614-26.

- Badanes LS, Watamura SE, Hankin BL. Hypocortisolism as a potential marker of allostatic load in children: Associations with family risk and internalizing disorders. Develop Psychopathol. 2011;23(3):881-896.

- Lovallo WR. Early life adversity reduces stress reactivity and enhances impulsive behavior: implications for health behaviors. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013;90(1):8-16.

- Bosch NM, Riese H, Reijneveld SA et al. Timing matters: long term effects of adversities from prenatal period up to adolescence on adolescents’ cortisol stress response. The TRAILS study. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2012;37(9):1439-1447.

- Nijhof SL, Rutten JMTM, Uiterwaal CSPM et al. The role of hypocortisolism in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2014;42:199-206.

- Tak LM, Cleare AJ, Ormel J et al. Meta-analysis and meta-regression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in functional somatic disorders. Biol Psychol. 2011;87(2):183-94.

- Van Hoof E, Cluydts R, De Meirleir K. Atypical depression as a secondary symptom in chronic fatigue syndrome. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61(1):52-5.

- Bauer ME, Wieck A, Lopes RP et al. Interplay between neuroimmunoendocrine systems during post-traumatic stress disorder: a minireview. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2010;17(3):192-5.

- Boscarino JA. A prospective study of PTSD and early-age heart disease mortality among Vietnam veterans: implications for surveillance and prevention. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(6):668.

- Yehuda R, Golier JA, Kaufman S. Circadian rhythm of salivary cortisol in Holocaust survivors with and without PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(5):998-1000.

- Henigsberg N, Folnegovic-Smalc V, Moro L. Stressor characteristics and post-traumatic stress disorder symptom dimensions in war victims. Croatian Med J. 2001;42(5):543-550.

- Delahanty DL, Raimonde AJ, Spoonster E. Initial posttraumatic urinary cortisol levels predict subsequent PTSD symptoms in motor vehicle accident victims. Biol Psych. 2000;48(9):940-947.

- Prousky J. Mild adrenocortical deficiency and its relationship to:(1) chronic fatigue syndrome;(2) nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and hyperemesis gravidarum; and (3) systemic lupus erythematosus. J Orthomol Med. 2012;27(4):165-176.

- Baschetti R. Chronic fatigue syndrome: a form of Addison’s disease. J Internal Med. 2000;247(6):737-739.

- Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengård B, Pedersen NL. Premorbid predictors of chronic fatigue. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(11):1267-1272.

About the Author

Lena Edwards MD, ABOIM, FAARM, ABAARM

Lena Edwards MD, ABOIM, FAARM, ABAARM

Edwards is an Internist who is also Board Certified in Integrative Medicine, Board Certified and Fellowship Trained in Anti-Aging & Functional Medicine, and Fellowship Trained in Integrative Cancer Therapy. She is also a fellow of the American Institute of Stress. Edwards’ is best recognized for her expertise in treating complex Integrative Medicine issues, male and female hormone imbalance, HPA axis and adrenal dysfunction, and stress related bodily disorders. In addition to her clinical practice, she has also been actively involved in writing, teaching, speaking, and consulting. She has served as a clinical instructor for the American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine, the Medical Metabolic Institute, and the George Washington University Integrative Medicine Program. Her professional affiliations include The American Board of Physician Specialties; The American Board of Integrative Medicine; The American Academy of Anti-Aging and Functional Medicine; The American Institute of Stress; The American College of Physicians; and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society.

Edwards has been selected as one of America’s Top Physicians in Internal Medicine, Integrative Medicine, Integrative Cancer Therapy, and as one of the Leading Integrative Medicine Physicians in the World by the International Association of HealthCare Professionals. She has also authored numerous articles for mass media outlets and peer-reviewed medical journals. Her self-authored book, Adrenalogic: Outsmarting Stress, has sold thousands of copies world-wide.

Editor’s note: William Edwards, a student in Boca Raton, Florida, assisted in review and research for this paper.