Using genetics in hormone balancing for women

By Katherine Shagoury

We no longer have to guess or assume when it comes to patient genetic information, said Wendy Warner, MD, FACOG, ABIHM, IFMCP, at the 2019 Integrative Healthcare Symposium in New York City.

Genetic testing is more sophisticated than ever. Many patients have already had genetic testing done to understand their own single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Practitioners can use this information to more easily tailor plans for hormone balancing in women, cutting to the chase so that each plan conforms to the individual we’re working with, Warner said.

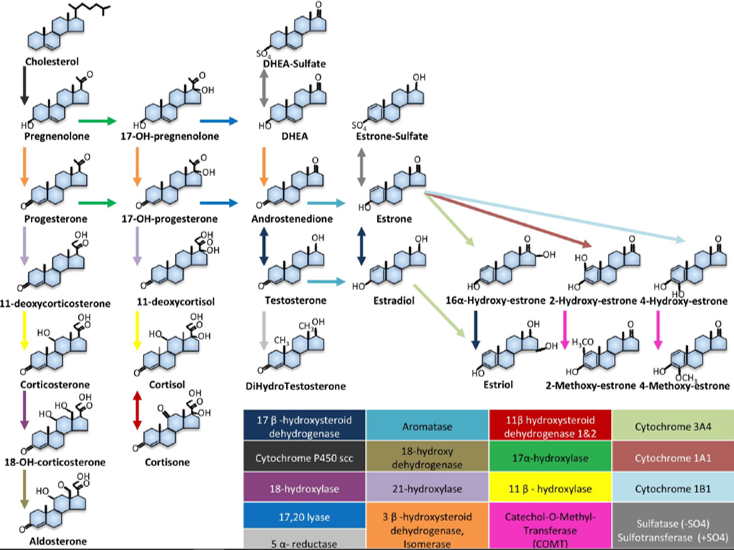

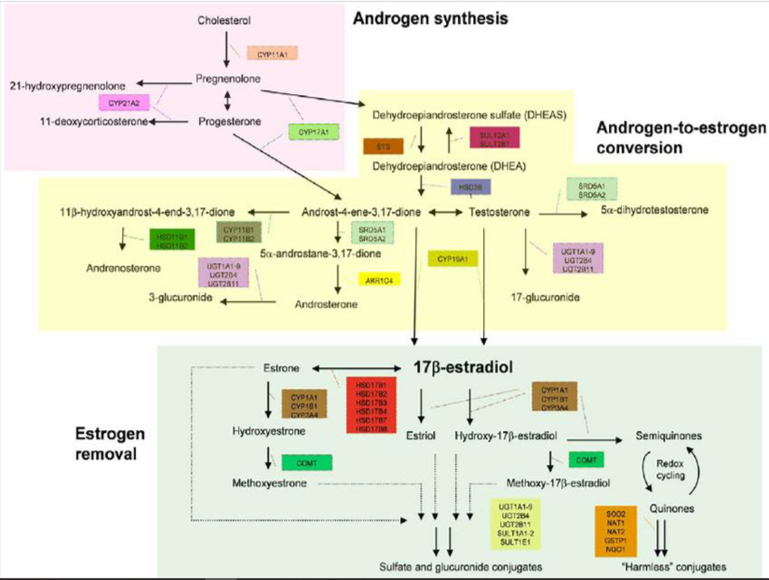

It’s impossible to talk about hormone balancing without first understanding the pathways, Warner said. She offers two graphics that practitioners can use for their own reference and when speaking with patients:

Hormone Pathways

Androgen and Estrogen

Warner highlighted a number of specific enzymes that may cause issues for patients:

- Cyp11A1

- Cyp17A1

- STS

- STS as NFKB targeted gene

- SULT 2A1/B1

- Cyp19A1

Cyp11A1 take cholesterol to pregnenolone. It is mostly active in the adrenals but has some activity in the ovaries and testes. Defects in this enzyme activity lead to androgen insufficiency, and plays a role in some allergies, including peanut allergies through effects on steroidogenesis, an essential pathway in Th2 differentiation, Warner said.

Cyp17A1 takes mineralocorticoids to glucocorticoids and makes 17,20 lyase, which takes glucocorticoids to sex hormones. A deficiency can lead to hypertension, primary amenorrhea, and low vitamin K levels in some patients.

STS takes DHEA sulfate to DHEA. If a patient has increased expression, they may have greater availability of estradiol in some cancers, including breast cancer, and increased hepatic expression with chronic inflammatory liver disease. It is an NFKB target gene. STS is also involved in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Expression is increased postpartum, and may lead to postpartum depression.

Inflammatory activation of NFKB induces STS gene expression, Warner said. This leads to increase active estrogens and attenuates NFKB-medication inflammation and negative feedback.

SULT 2A1/B1 takes DHEA to DHEA sulfate and is highly expressed in the adrenals and liver. For patients with a high rate of polymorphisms, they may experience a change in DHEA and DHEA sulfate ratio, which may correlate with a high risk of prostate cancer. Hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls are substrates and inhibitors, and compete with our own hormones, Warner said.

Cyp19A1 is aromatase, and takes androstenedione to estrone, and testosterone to estradiol. Some SNPs in this enzyme are associated with polycystic ovary syndrome, while others lead to lower flashes with Tamoxifen. Some SNPs can increase levels of E2 and E3 as well.

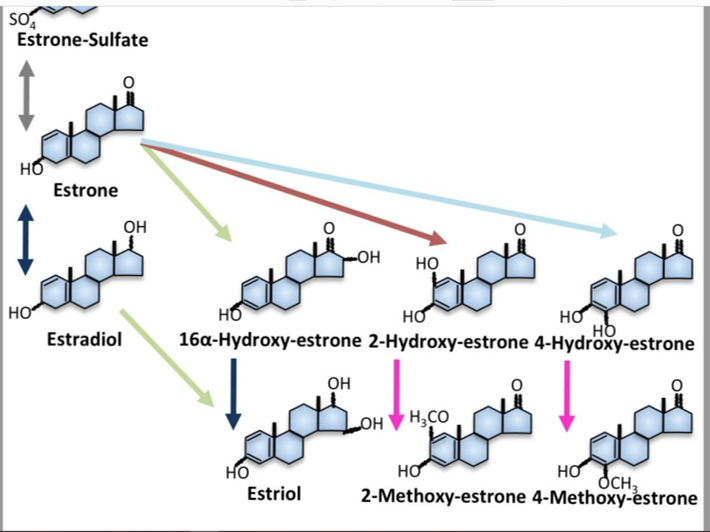

Once you make it through the pathway to estrogen, practitioners must understand estrogen breakdown. This is where the rubber meets the road, Warner said. If a patient is not making the appropriate estrogen breakdown products, and totally methylating and getting rid of them, they’re going to be in trouble.

Estrogen is highly inflammatory, and our livers get rid of it in the same way as toxins. Methylation is an often-overlooked component of hormone balancing but it is critical to look at the full detoxification. Warner offers this graphic to illustrate how estrogen is broken down:

Estrogen Breakdown

Phase 1 of estrogen breakdown creates several free radicals and inflammation. It takes estrogen to hydroxylation and these are the enzymes involved:

- Cyp3A4 to 16 hydroxylation

- Cyp1A1 to 2 hydroxylation

- Cyp1B1 to 4 hydroxylation

In Phase II, the hydroxylated products are further broken down through methylation, glucuronidation, sulfation, or turning quinones into “harmless” conjugates, Warner said.

Once a practitioner understands hormone pathways and how estrogen is broken down, they can begin to play with the information to change genetic expression in practice. One of the easiest ways to influence genetics and hormones is to look at what we’re eating, Warner said. The diet is a mix of carcinogens, mutagens, and protective elements. All are metabolized by the same enzymes.

To start making dietary adjustments, Warner says practitioners must adjust in order—increasing Phase I without increasing Phase II will lead to increased inflammation and free radicals.

In general, work towards a more anti-inflammatory diet, Warner said. Suggest patients eat the whole food—broccoli florets, stems, and leaves, for example—and include plenty of fiber, lignans, resveratrol and green tea, quercetin, and various herbs.

There are two types of tests practitioners can use to start addressing genetic information in their practices, partial testing and whole genome testing. Partial testing is more common, and often more affordable, but whole genome testing offers a broader picture of what is really going on in a patient’s genetics and hormone levels.

Overall, practitioners who want to incorporate genetic information into their patient exams, beyond having the proper training, need to be cognizant of what the results are really telling them about their patient’s health, because it is complex and not always black and white.

“For practitioners who are new at talking to patients about genetic information, please be careful with the big picture,” Warner said. “There is nothing worse than saying to somebody, you have this SNP that’s a problem, and you forget to tell them they have another SNP that counteracts it. It usually balances out and you only have to worry about a couple of things.”