Computers, television, handheld devices risk factors for insomnia?

By Bill Reddy, LAc, DiplAc

Chronic insomnia can lead to serious problems. We consolidate memories, heal our bodies, generate stem cells, remove neurotoxic waste products, and mitigate pro-inflammatory cytokines when we sleep. The current medical literature is rich with repercussions of sleep deprivation, such as coronary heart disease, a higher tendency toward injury, weight gain, accidents, and a generally diminished sense of wellbeing accompanied by decreased immune system function.

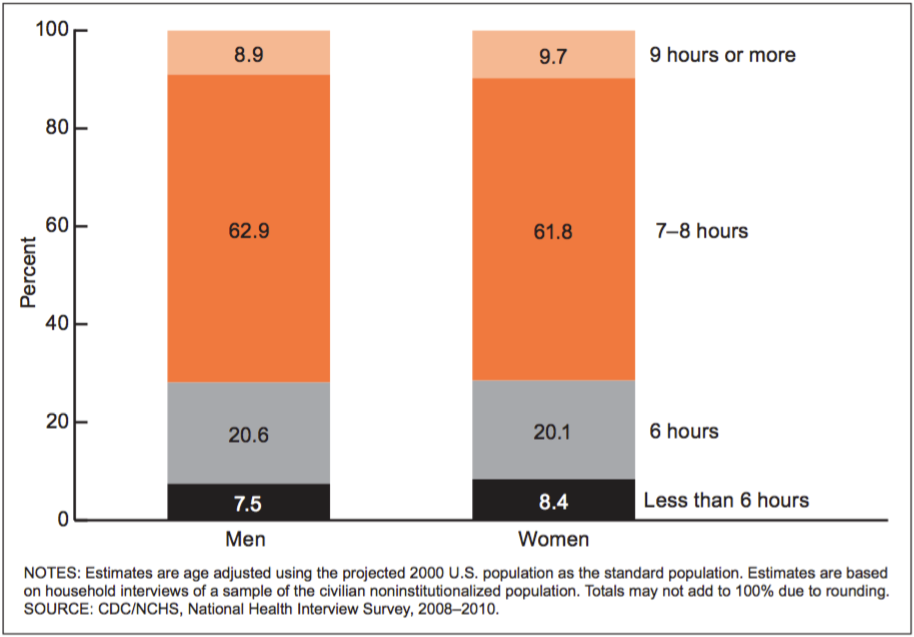

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), school-aged children and teenagers need at least nine hours of sleep, and adults and seniors need seven to eight hours. In a 2008-2010 National Health Interview survey, 28.3 percent of adults admitted to getting less than six hours of sleep per night, which is far from optimal. Not surprisingly, adults between 25 and 64 years old were most likely to sleep six hours or less. Too much sleep can trigger inflammatory chemicals leading to chronic disease, so we have to work within a “sweet spot” depending on our patient’s age and personal needs.

Percent distribution of hours of sleep in a 24-hour period, by sex: United States, annualized, 2008–2010. Image by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

It’s likely insomnia patients aren’t suffering from a benzodiazapine deficiency, and the treatment of chronic insomnia with any kind of drug is a dangerous proposition. From 2005 to 2016, the number of deaths in the U.S. due to benzodiazapines nearly tripled. Adding a benzodiazepine medication to any opioid can be deadly. More than 30 percent of opioid deaths involve benzodiazepines, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Anticholinergic medications have been linked to brain shrinkage and dementia. In 2013, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that manufacturers of Ambien (zolpidem), classified as a hypnotic, lower the recommended dosage due to “next-morning impairment” making driving risky. Common adverse reactions of this class of drug include headache, dizziness, nausea, dysmenorrhea, tremor, abdominal pain, and ocular pain. More severe, but less common side effects include visual impairment, ocular hemorrhage, hearing loss, retinal detachment, peptic ulcer, bronchospasm, apnea, pleural effusion, corneal erosion, pulmonary embolism, pericardial effusion, ventricular tachycardia, and cyanosis.

Number of Deaths in the U.S. due to Benzodiazapines. Image by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Television and computer monitor screens have grown in size and brightness over the past decade, blasting our eyeballs with light. Even the light from a cell phone is enough to inhibit the release of melatonin in our brains. Nocturnal melatonin suppression is most sensitive to short wavelength blue light, approximately 460 nanometers, emitted from screens.

In the National Sleep Foundation’s 2011 Sleep in America poll, 95 percent of the respondents used some kind of electronic device a few nights per week within an hour before going to sleep, and 48 percent used a computer, tablet, or smart phone in bed before going to sleep. In addition, 21 percent of American adults, representing 52 million people, who reported awakening from sleep and using an electronic device before trying to go back to sleep at least once in the past seven days.

Recently published evidence indicates that the electromagnetic field (EMF) generated by charging your cellphone or other device near the head of your bed may endanger sleep quality. The EMF exposure from phone use during the day will impede sleep if you do not use corded headphones or ear buds. WiFi is also a culprit according to Martin Pall, Professor emeritus of biochemistry and basic medical sciences at Washington State University in Portland, Oregon. Experts suggest turning off the modem before sleep.

For those patients who are in the habit of checking email or using any light-emitting device right up until bedtime, recommend they install a “blue filter” application on the phone, tablet, or computer or purchase blue filter glasses. Common sleep hygiene recommendations include going to sleep and waking at the same time every day, sleeping in a cool, dark room and hiding the clock, to keep insomniacs from peeking during the night. Even the light from an LED clock can disturb sleep. Placing two tennis balls in a sock, tying a knot, and placing them under the occiput—at anmian, “Jade pillow” acupoints—for several minutes can help promote somnolence.

Supplements such as melotonin (300 micrograms to 10 milligrams) or 5-HTP (100 milligrams) before bedtime can be helpful, however 5-HTP is contraindicated for those who are taking anti-anxiety medications or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Women should be checked for iron and copper deficiencies, as both will interfere with quality sleep.

If your patient complains of being physically exhausted before bed, but their brain “won’t turn off,” recommend L-Theanine, which increases gamma-Aminobutyric acid and alpha brain wave activity. Studies on L-Theanine have used doses as low as 50 milligrams, but more frequently between 200-250 milligrams 30-60 minutes before bedtime with no grogginess upon waking. A seven-ounce cup of green tea contains roughly 8 milligrams of L-theanine, and black tea about 25 milligrams, however, both contain caffeine which wouldn’t be advisable to drink right before bedtime. Both may be consumed during the day.

In the future, please keep in mind the negative effect of EMF exposure and light emanating from various devices on your patients’ sleep quality.

References

Ayas, N. T., White, D. P., Manson, J. E., Stampfer, M. J., Speizer, F. R., Malhotra, A., & Hu, F. B. (2003). A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 205–209.

Barnes, C. M., & Wagner, D. T. (2009). Changing to daylight saving time cuts into sleep and increases workplace injuries. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1305–1317

Blask D.E. (2009) Melatonin, sleep disturbance and cancer risk. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 13(4), 257–264.

Campbell N, Boustani M, Limbil T, et al. (2009)The cognitive impact of anticholinergics: a clinical review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. (1):225-233.

Doyle P. (2017) What’s Ailing You? Your Guide on the Issues and Solutions of Manmade Radiation. Annapolis, MD: Candid Wellness Inc.

Drake, C. L., Roehrs, T. A., Burduvali, E., Bonahoom, A., Rosekind, M., & Roth, T. (2001). Effects of rapid versus slow accumulation of eight hours of sleep loss. Psychophysiology, 38, 979–987.

National Sleep Foundation. (2017) Sleepless Tech Users Sacrifice Sleep Health. Retrieved April 11, 2019. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/press-release/sleepless-tech-users-sacrifice-sleep-health.

Lanage K, Johnson R, Barnes C. (2014) Beginning the workday yet already depleted? Consequences of late-night smartphone use and sleep. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 124(1):11-23

Minkel, J. D., Banks, S., Htaik, O., Moreta, M. C., Jones, C. W., McGlinchey, E. L., Dinges, D. F. (2012). Sleep deprivation and stressors: Evidence for elevated negative affect in response to mild stressors when sleep deprived. Emotion, 12, 1015–1020.

Pall M.L. Microwave frequency electromagnetic fields (EMFs) produce widespread neuropsychiatric effects including depression. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2016;75:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2015.08.001.

Schoenborn CA, Adams PE, Peregoy JA. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2008-2010. Vital Health Stat. 2013 May;(257):1-184

Talbot, L. S., McGlinchey, E. L., Kaplan, K. A., Dahl, R. E., & Harvey, A. G. (2010). Sleep deprivation in adolescents and adults: Changes in affect. Emotion, 10, 831–841.