Reflections on the Sidney Project: Can We Talk? Can We Give Voice to the Taboo Topics That Are Usually Not Embraced in Residency Medical Education?

by Janet Lynn Roseman, PhD, R-DMT, MS

The entire Universe is condensed in the body, and the entire body in the Heart. Thus the Heart is the nucleus of the whole Universe. —Sri RamanaMaharshi 1

Prelude My life changed after witnessing the death of my father, Sidney, who passed away in 2009 at the hands of a wounded medical culture that in my opinion refused to acknowledge that his life was a life worth saving. This horrific tragedy came on the heels of the death of my mom, who I also adored. After my mother’s passing, I had the opportunity to know my dad from the bones and saw his softer side emerging. His presence was a soothing balm for me, as I struggled to inhabit a world without her. My dad had always been my rock; however, now, we had a closer bond, firmly rooted, and that bond continues although he is not physically present. I was driven to take action in an effort to guide physicians to remember their sacred oath to ‘‘first, do no harm.’’ It was my hope that through reflective education another daughter could be spared from navigating the same journey that I experienced. This paper discusses the Sidney Project in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care, and briefly explores the concept of Jung’s ‘‘wounded healer’’ as a rich source of physician’s self-reflection and subsequent empowerment and the author’s belief of its foundational importance in medical education. During the Sidney Project program, residents explored these wounds through dialogue, somatics, meditation and arts-based techniques.

The Sidney Project

I created the Sidney Project in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care to provide physician residents an opportunity to receive training and awareness of the significance of spirituality, compassionate care and caring in the medical encounter. The program offered 16 participants from various disciplines opportunities to explore and reflect on compassionate medical training, including hands-on guidance and tools for the integration of spirituality and compassionate medicine into daily patient encounters. Participants also learned strategies for improving the patient/physician relationship and candidly discussed with peers their fears, joys and concerns in a safe environment cultivated over three months of weekly meetings held at two hospitals in South Florida: Broward Health Medical Center and University Hospital. The program included residents from several disciplines at Broward Health whereas the participants at University Hospital were all residents in the psychiatry program. Participants completed a pre and post survey identifying their previous experiences with the subject matter; at the end of the program, they presented papers based on their research on any aspect of spirituality and medicine and compassionate care that they were drawn to. They also received certificates of completion. I was fortunate to find a great deal of support to orchestrate the program and I am grateful to Dr. Joseph DeGaetano, Dr. Mariaelena Caraballo and Dr. Natasha Bray for their encouragement and for opening the doors to this project.

Various themes were discussed including:

- Self-Care and Self-Renewal

- Rediscovering the Soul of Compassionate Medicine

- The Power of Healing

- Revisiting the Osteopathic Oath of Healing

- The Asklepian Tradition and the Wounded Healer

- Patient Centered Interviewing Skills

- Humanistic Excellence: Presence, Silence, and Connection

- Breaking Bad News

- The Role of Spirituality in Medicine

- Art Therapies in Medicine

I hoped that by creating a safe forum where physician residents could share narratives and challenging patient encounters that explored the human side of illness, they could not only acquire and discuss self-care strategies, but discuss their emotional terrain with peers including the taboo topics such as physician woundedness and beliefs about the mythology of physicians. It was hoped that through this exploration they could develop a keener consciousness of the importance of compassionate medicine. It is noteworthy that participants cited that the sharing of stories about both patient connection and the failure to make these connections was important to discuss and honor with peers.

In my experience as teacher and therapist, the creation of safe space is not something that can be organized or taught, it is cultivated. I believe it is a sacred interchange created by participants who feel enough trust and respect for their colleagues to share their experiences and opinions openly, knowing that their point of view will be witnessed and most importantly heard and received. This sense of trust evolves organically and is often communicated nonverbally through an energetic exchange so people know, deeply in their core, that it is safe to speak and that they will not be judged. To feel that one can communicate one’s authentic story and that it was heard and received and could make a difference in another person’s life is always a blessing. The cultivation of such sacred space in medicine I believe can help remind physicians that their work can be a spiritual practice if they choose.

Echoing Native American philosopher Eber Hampton, ‘‘Health practitioners must be concerned with spirituality, at the center of which is respect for the relationships that exist between all things. We must nurture these spiritual relationships and allow them to work on us.2’’ The creation of these ‘‘spiritual relationships’’ between physician residents and their patients was a goal for the Sidney Project. It is significant that when residents had the opportunity to share their narratives withmembers of the group candidly and in an environment of trust, these ‘‘spiritual relationships’’ could flourish and provide nurturance for participants. Such nurturance is foundational for physicians and can offer the chance to improve the physician/patient encounter.

In a study on compassionate patient care, Anandarajah and Roseman found that it was possible for physicians to see ‘‘medicine as providing opportunities for them to grow in compassion, essentially employing medicine as a spiritual discipline.3’’ This consciousness of compassion and chance to integrate medical practice as a spiritual discipline also can be a natural conduit for the cultivation of self-compassion. The idea of physician self-care is not new; however, providing a forum that includes both the light and the shadow emotions of patient care experiences can be an important part of physician self-care. I would strongly suggest that it is not only important but it should be required training in all residency medical education to provide for a safe forum to discuss such narratives without fear of being judged by supervisors and peers in order to prevent the projection of one’s own wounds on the patient-physician encounter. As psychotherapist Carl Jung stated at the end of his life, ‘‘Only if the doctor knows how to cope with himself and his own problems will he be able to teach the patient to do the same.4’’

Although the Sidney Project addressed many topics, feedback from the participants indicated that the opportunities to talk about patient cases and share ‘‘real feelings’’ in small group settings were most meaningful. At the end of the program, one resident said, ‘‘Thank you for sharing your thoughts and opening up and sharing stories. It’s been a pleasure getting to know you all better. Our discussions are what I enjoyed the most.’’

According to Natasha Bray, DO, MS, Director of Medical Education at Broward Health, ‘‘The spirituality in medicine course allowed residents to bond together and feel supported in exploring the challenges with keeping humanism in a highly scientific and often depersonalized medical establishment. Little time in medical education is set aside for reflection on how treatment plans often challenge the very core of our patients. The loss of privacy and dignity is often given little attention as patients are shuffled through a busy clinical day. Equally neglected is the emotional stress and turmoil that physicians in training experience in the lack of time that is devoted to thoughtful reflection on the lives that we touch. Physicians are taught to compartmentalize their emotional response to allow for clear thinking in the care of patients. While this is often necessary in themoment, they are taught to not experience the human connection with their patients and therefore damaging the sacred patient-physician relationship.’’ Such compartmentalization often erodes the physicians’ opportunities for self-care and reflection and the chance to discuss openly the mythology of being perfect (an unrealistic expectation for any profession) was very important to participants.

As Elena Avila states, ‘‘Western medical practices traditionally exclude the soul and spirit. As the ‘science’ of medicine has gone forward in this century, the care of the human has become very compartmentalized. The body goes to the doctor, the mind to the psychiatrist and the soul and spirit to the church or synagogue .. If we want true and lasting wellness, we cannot leave the soul outside of the hospital and the doctor’s office. I carry my soul and my spirituality with me everywhere I go, because I know that I am more than a body.5’’ Such exclusion of the soul and spirit is not confined to patients, and physicians are at greater risk of this depersonalization because of the medical culture that supports such divisions.

Mariaelena P. Caraballo, DO, FAAHPM, Director of Medical Education at University Hospital & Medical Center, reflected, ‘‘Psychiatrists daily are helping their patients cope with a variety of psychiatric issues. They need to look into themselves as well. I recently mentioned to a psychiatrist friend that if he continues his current work schedule that he is going to have a stroke as he continues to work most days until 10 p.m. We as health professionals need to take the time to take care of ourselves; to take a few minutes off during the day to relax whether it be through exercise, meditation or reading. This ability to be introspective and address how we are currently feeling helps us better help our patients. An individual that is facing personal stress will not be able to listen and assist (patients) as intently. Residents participate in ‘process groups’ to help them discuss and deal with the thoughts and emotions evoked during a patient treatment session. These meetings may not occur when most needed or the residents may not feel comfortable sharing those feelings. The Sidney Project sessions have helped them to not only be open to discuss feelings and spirituality with their patients but to be open to discussions among themselves. Last year residents presented cases that incorporated bio-psychosocial aspects involving not only the patients’ underlying psychiatric disorder but underlying social and spiritual issues. One resident commented that ‘understanding the bio-psychosocial- spiritual aspects of a patient is essential to a psychiatrist to facilitate healing.’’’ Such ‘‘healing’’ is not confined for patients.

Carl Jung’s concept of the wounded healer is cemented in depth psychology training, offering the wisdom that one’s internal wounds could be empowering in the patient/physician encounter. Asklepius is considered an ancient father of modern medicine and a ‘‘wounded healer.’’ Asklepius, whose name means ‘‘cut open,’’ was seized from his mortal mother’s body while she lay burning on a funeral pyre that his mythological father, Apollo, commanded because of his wife’s infidelity. Filled with remorse, Apollo saved the young baby and gave him to Chiron, master physician, who provided Asklepius’ training in both suffering and healing. Chiron was no stranger to acute woundedness, spending most of his life in excruciating pain. He was wounded by an arrow shot by Hercules, and later placed in the sky as the Centaur constellation Sagittarius, and was freed from constant suffering. Asklepian teachings have relevance in today’s medical training for as both Victor Frankl’s and the Buddha’s writings depict, ‘‘suffering is fundamental to human experience’’ and part of the journey of life. The provision of protected space to discuss one’s woundedness and need for self-care is pivotal and needs to be included as a necessary and welcome aspect of clinician training. When we ignore, negate and minimize the sufferings of physicians, the culture upholds a mythology of dysfunction. Medicine is a profession filled with suffering and pain; however, it is imperative to acknowledge physicians’ pain and suffering in appropriate venues and offer medical education that provides sanctuary to discuss these often taboo subjects.

According to Dr. Caraballo, ‘‘One of the Sidney Project’s goals was to teach residents the importance of self-care. One of the assignments was on how to use a ‘worry stone.’ I still have mine on my desk. It is curious how during times of stress or worry my hand gravitates towards the stone. I hold it, smile and put it down. It works.’’ When self-care is not acknowledged, physicians do not have the opportunity to find balance and wholeness. This void often speaks to patients both consciously and unconsciously. How can you offer compassionate care to patients if you do not embody it first with self? The archetype of woundedness is not without its gifts. Although, it is usually believed that our wounds makes us weak (especially in medicine), this is false. Our woundings are wisdom and remembrance of both our humanity and vulnerability. Wounds also can be sources for empowerment if we give them voice. Without such voice, physicians are denied the chance to find one’s soul voice to reveal the mysteries of subsequent healing that this voice may offer. I am a ‘‘wounded healer’’ and I know the value of those wounds for they arrived at an incalculable price.

Curricula that includes ‘‘formats that include personal reflection may be a powerful way to convene and experience the fuller dimension of spirituality . so that they in turn can have a greater appreciation for spirituality in their patient’s lives. Translating theory into practice requires more than just the assimilation of knowledge . and needs supporting with the formation through reflective practice and learning from the wisdom and tacit knowledge of a community of practice.6’’ Such ‘‘lived experiences’’ offer the enduring key for authentic remembrance.

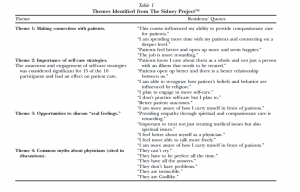

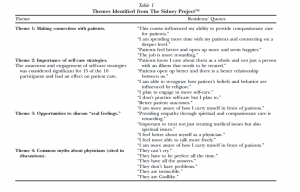

Conclusion Residents who were involved with the Sidney Project indicated that their participation helped them become more aware of compassionate medical practices, which they were able to integrate in patient care despite the diversity of beliefs among them. The themes that emerged offer validation of the beneficial aspects of this program and other curricula in spirituality and medicine including: ‘‘deeper connection to patients,’’ ‘‘importance of selfcare strategies,’’ and a ‘‘consciousness of the connection between physician and patient.’’ These themes are further identified in Table 1. When doctors honestly discuss the common myths and psychic pressures of their profession openly, they can serve as potent ‘‘models’’ for younger physicians. Based on the data from the program, I would suggest that these opportunities to discuss ‘‘real’’ feelings about patient encounters and this ‘‘yearning for connection’’ with patients are part of the concept of ‘‘the wounded healer.’’ The idea that such discussions cannot only offer self-reflection but provide a much needed forum for physician self-healing is implicit. How many have chosen their profession not only to make a difference but for personal soul healing? Can we talk? Further study is planned in the future with additional yearlong residency programs at various sites. The Sidney Project recently received a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation to continue this program.

Acknowledgments This article is dedicated to my father, Sidney.

References - Ramana Maharshi S. The heart. Parabola 2001; 26:79.

- Mehl-Madrona L. Narrative medicine: The use of history and story in the healing process. New York: Bear and Company, 2007:299.

- Anandarajah G, Roseman JL. A qualitative study of physician’s views on compassionate patient care and spirituality: medicine as a spiritual practice. R I Med J 2014;97:17e22.

- Jung C. Memories, dreams, reflections. New York: Vintage Books, 1963/1909.

- Avila E. Woman who glows in the dark: a curandera reveals traditional Aztec secrets of physical and spiritual health. New York: Tarcher/Putnam, 2000:171.

- Puchalski C, Cobb M, Rumbold B. Part 1: Curriculum development in spirituality and health in the health professions. In: Cobb M, Puchalski C, Rumbold B, eds. Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012:426.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management published by Elsevier in September 2014. The author obtained all required and appropriate permissions allowing us to share and publish this work. Sidney Project in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care and Sidney Project are registered trademarks.  I created the Sidney Project in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care to provide physician residents an opportunity to receive training and awareness of the significance of spirituality, compassionate care and caring in the medical encounter. The program offered 16 participants from various disciplines opportunities to explore and reflect on compassionate medical training, including hands-on guidance and tools for the integration of spirituality and compassionate medicine into daily patient encounters. Participants also learned strategies for improving the patient/physician relationship and candidly discussed with peers their fears, joys and concerns in a safe environment cultivated over three months of weekly meetings held at two hospitals in South Florida: Broward Health Medical Center and University Hospital. The program included residents from several disciplines at Broward Health whereas the participants at University Hospital were all residents in the psychiatry program. Participants completed a pre and post survey identifying their previous experiences with the subject matter; at the end of the program, they presented papers based on their research on any aspect of spirituality and medicine and compassionate care that they were drawn to. They also received certificates of completion. I was fortunate to find a great deal of support to orchestrate the program and I am grateful to Dr. Joseph DeGaetano, Dr. Mariaelena Caraballo and Dr. Natasha Bray for their encouragement and for opening the doors to this project. Various themes were discussed including:

I created the Sidney Project in Spirituality and Medicine and Compassionate Care to provide physician residents an opportunity to receive training and awareness of the significance of spirituality, compassionate care and caring in the medical encounter. The program offered 16 participants from various disciplines opportunities to explore and reflect on compassionate medical training, including hands-on guidance and tools for the integration of spirituality and compassionate medicine into daily patient encounters. Participants also learned strategies for improving the patient/physician relationship and candidly discussed with peers their fears, joys and concerns in a safe environment cultivated over three months of weekly meetings held at two hospitals in South Florida: Broward Health Medical Center and University Hospital. The program included residents from several disciplines at Broward Health whereas the participants at University Hospital were all residents in the psychiatry program. Participants completed a pre and post survey identifying their previous experiences with the subject matter; at the end of the program, they presented papers based on their research on any aspect of spirituality and medicine and compassionate care that they were drawn to. They also received certificates of completion. I was fortunate to find a great deal of support to orchestrate the program and I am grateful to Dr. Joseph DeGaetano, Dr. Mariaelena Caraballo and Dr. Natasha Bray for their encouragement and for opening the doors to this project. Various themes were discussed including:  According to Dr. Caraballo, ‘‘One of the Sidney Project’s goals was to teach residents the importance of self-care. One of the assignments was on how to use a ‘worry stone.’ I still have mine on my desk. It is curious how during times of stress or worry my hand gravitates towards the stone. I hold it, smile and put it down. It works.’’ When self-care is not acknowledged, physicians do not have the opportunity to find balance and wholeness. This void often speaks to patients both consciously and unconsciously. How can you offer compassionate care to patients if you do not embody it first with self? The archetype of woundedness is not without its gifts. Although, it is usually believed that our wounds makes us weak (especially in medicine), this is false. Our woundings are wisdom and remembrance of both our humanity and vulnerability. Wounds also can be sources for empowerment if we give them voice. Without such voice, physicians are denied the chance to find one’s soul voice to reveal the mysteries of subsequent healing that this voice may offer. I am a ‘‘wounded healer’’ and I know the value of those wounds for they arrived at an incalculable price. Curricula that includes ‘‘formats that include personal reflection may be a powerful way to convene and experience the fuller dimension of spirituality . so that they in turn can have a greater appreciation for spirituality in their patient’s lives. Translating theory into practice requires more than just the assimilation of knowledge . and needs supporting with the formation through reflective practice and learning from the wisdom and tacit knowledge of a community of practice.6’’ Such ‘‘lived experiences’’ offer the enduring key for authentic remembrance. Conclusion Residents who were involved with the Sidney Project indicated that their participation helped them become more aware of compassionate medical practices, which they were able to integrate in patient care despite the diversity of beliefs among them. The themes that emerged offer validation of the beneficial aspects of this program and other curricula in spirituality and medicine including: ‘‘deeper connection to patients,’’ ‘‘importance of selfcare strategies,’’ and a ‘‘consciousness of the connection between physician and patient.’’ These themes are further identified in Table 1. When doctors honestly discuss the common myths and psychic pressures of their profession openly, they can serve as potent ‘‘models’’ for younger physicians. Based on the data from the program, I would suggest that these opportunities to discuss ‘‘real’’ feelings about patient encounters and this ‘‘yearning for connection’’ with patients are part of the concept of ‘‘the wounded healer.’’ The idea that such discussions cannot only offer self-reflection but provide a much needed forum for physician self-healing is implicit. How many have chosen their profession not only to make a difference but for personal soul healing? Can we talk? Further study is planned in the future with additional yearlong residency programs at various sites. The Sidney Project recently received a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation to continue this program. Acknowledgments This article is dedicated to my father, Sidney. References

According to Dr. Caraballo, ‘‘One of the Sidney Project’s goals was to teach residents the importance of self-care. One of the assignments was on how to use a ‘worry stone.’ I still have mine on my desk. It is curious how during times of stress or worry my hand gravitates towards the stone. I hold it, smile and put it down. It works.’’ When self-care is not acknowledged, physicians do not have the opportunity to find balance and wholeness. This void often speaks to patients both consciously and unconsciously. How can you offer compassionate care to patients if you do not embody it first with self? The archetype of woundedness is not without its gifts. Although, it is usually believed that our wounds makes us weak (especially in medicine), this is false. Our woundings are wisdom and remembrance of both our humanity and vulnerability. Wounds also can be sources for empowerment if we give them voice. Without such voice, physicians are denied the chance to find one’s soul voice to reveal the mysteries of subsequent healing that this voice may offer. I am a ‘‘wounded healer’’ and I know the value of those wounds for they arrived at an incalculable price. Curricula that includes ‘‘formats that include personal reflection may be a powerful way to convene and experience the fuller dimension of spirituality . so that they in turn can have a greater appreciation for spirituality in their patient’s lives. Translating theory into practice requires more than just the assimilation of knowledge . and needs supporting with the formation through reflective practice and learning from the wisdom and tacit knowledge of a community of practice.6’’ Such ‘‘lived experiences’’ offer the enduring key for authentic remembrance. Conclusion Residents who were involved with the Sidney Project indicated that their participation helped them become more aware of compassionate medical practices, which they were able to integrate in patient care despite the diversity of beliefs among them. The themes that emerged offer validation of the beneficial aspects of this program and other curricula in spirituality and medicine including: ‘‘deeper connection to patients,’’ ‘‘importance of selfcare strategies,’’ and a ‘‘consciousness of the connection between physician and patient.’’ These themes are further identified in Table 1. When doctors honestly discuss the common myths and psychic pressures of their profession openly, they can serve as potent ‘‘models’’ for younger physicians. Based on the data from the program, I would suggest that these opportunities to discuss ‘‘real’’ feelings about patient encounters and this ‘‘yearning for connection’’ with patients are part of the concept of ‘‘the wounded healer.’’ The idea that such discussions cannot only offer self-reflection but provide a much needed forum for physician self-healing is implicit. How many have chosen their profession not only to make a difference but for personal soul healing? Can we talk? Further study is planned in the future with additional yearlong residency programs at various sites. The Sidney Project recently received a grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation to continue this program. Acknowledgments This article is dedicated to my father, Sidney. References

SHARE